Rethinking Computing Itself

“The fundamental building blocks of our world are quantum mechanical, if you look at a molecule, the reason molecules form and are stable is because of the interactions of these electron orbitals. Each calculation in there, each orbital, is a quantum mechanical calculation” Dario Gil, VP for science and solutions at IBM Research [4]

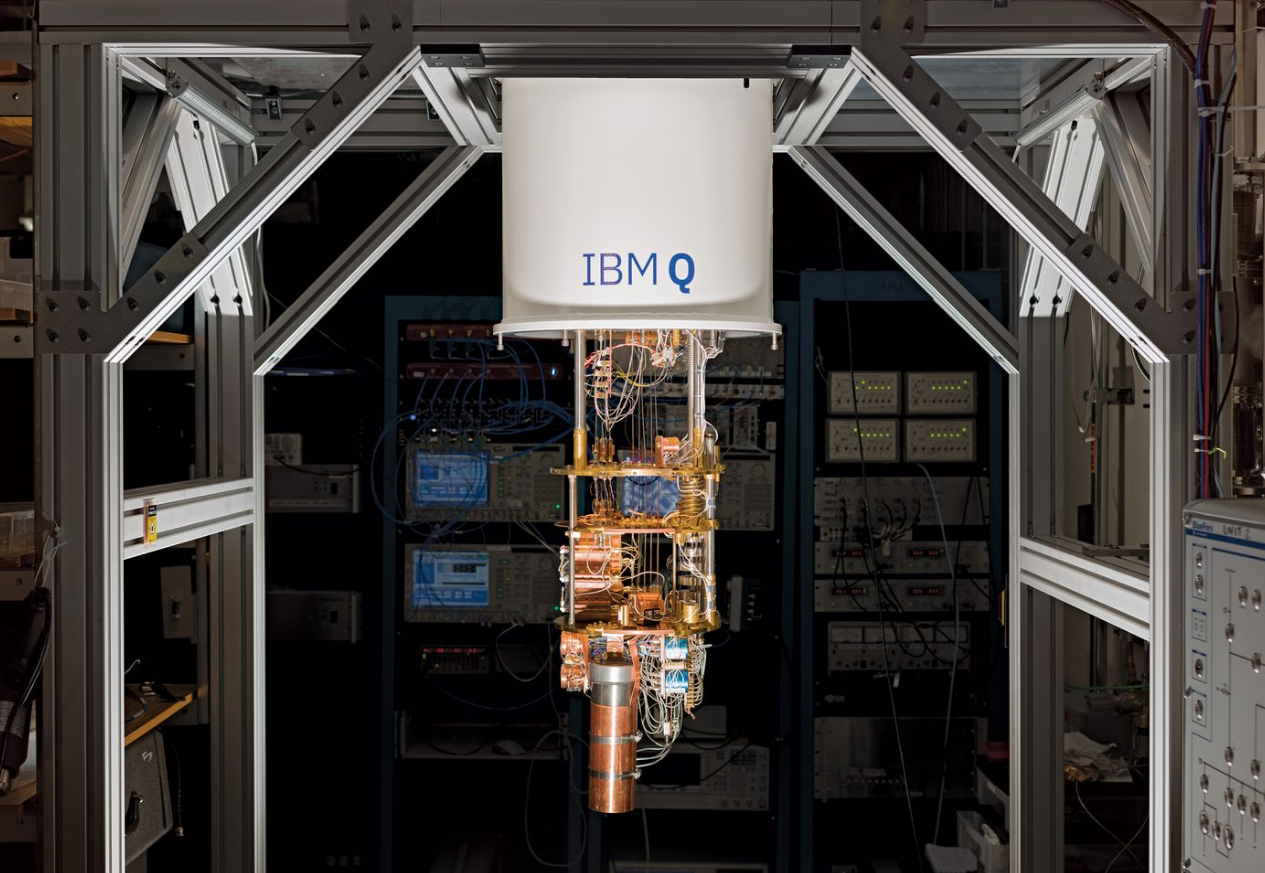

Since the world’s first digital computers were designed, built and commercialized in 1946, advances in semiconductors, programming and architecture have allowed us to solve some of the world’s most complicated problems. [1] Despite these advances one thing never changed, conventional digital computers are based on binary logic. This means that data needs to be encoded into binary digits, which are always in one of two definite states (0 or 1). We’ve been able to write complex algorithms and design microprocessors based on this configuration but many aspects of our everyday world such as chemical reactions with large molecules are not optimally described by conventional computers based on binary digits. Over three decades ago, Richard Feynman (a physicist) proposed using quantum processors that are built to mimic a blend of classical states simultaneously. [2] The question now becomes, where do we go from here? While large tech giants like Google and IBM are battling for quantum supremacy (the point where a quantum computer can perform a well-defined computational task beyond the capabilities of a conventional computer), a feat Google hopes to achieve by the end of 2017. [5] There are well established start-ups like D-Wave that hope use a combination of quantum and classical approaches to win the proverbial race.

Though the commercialization of quantum computers is still years away, it’s easy to suppose potential areas where they could provide value. The first is quantum simulation; the modelling of chemical reactions and materials is already a big business for companies like Boeing and Dow-DuPont. Whether it’s to develop new high strength polymers for airplanes or more efficient materials for solar cells, the ability to shift research processes from the qualitative and descriptive to the quantitative and predictive could unlock development pipelines bringing enormous value to society. The second is quantum optimization; the issues with classical algorithms are that they navigate through the landscape of possible solutions at a slow pace; optimal solutions may be hidden behind high barriers that are hard to overcome. By finding the highest quality solutions to problems like optimizing the routes for a fleet of FedEx trucks delivering packages across the country, companies are able to reduce costs and provide better service. The third is quantum sampling. Sampling from probability distributions is widely used in statistics and machine learning today. The ability to improve the speed at which we can process these problems could significantly improve performance and costs. [2]

The implications of advances in quantum computing are hard to predict and depend on the speed at which we are able to develop and commercialize these technologies. Quantum computers are great at solving certain types of problems but the reality is they aren’t required to process many of the computations we perform for everyday tasks. Existing data centers are unlikely to move completely towards quantum architecture and are more likely to add these capabilities for enterprises that have specific needs as a value added service. We won’t know the true value of quantum computers until quantum hardware becomes sufficiently powerful and accessible to enterprises and experts around the world. It’ll only be then will we be able to test and develop new types of algorithms that hope to solve some of the most complex phenomena we encounter today.

References:

[2] https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/45919.pdf

[6] https://www.dwavesys.com/sites/default/files/D-Wave_TR_14-1003A-D.pdf

Users who have LIKED this post: