Cybersecurity: Industrial Control Systems and the U.S. Electric Grid

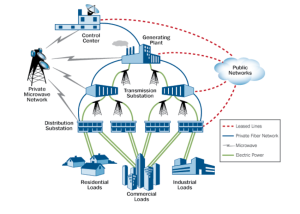

The U.S. electric grid, critical to supporting modern conveniences and enabling the enjoyment of a high standard of living, is dependent on a layered grid architecture including generation of power, transmission over two hundred thousand miles of power lines, and distribution to businesses and residences.1 When originally established, generation was accomplished via mechanical devices and processes that were manually controlled. With the advent of mid-range computers, particularly minicomputers of the 1960’s such as Digital Equipment Corporation’s 12-bit PDP-8, digital process control made possible the development and use of Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems to better control transmission and distribution.

By the late 1970’s, utility operators began incorporating Industrial Control System (ICS) variants to provide superior plant control, efficiency, automated grid synchronization of generators, etc. Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) from firms such as Allen-Bradley were used to automate electronic relays through ladder logic programming, versus using manual switching to activate or de-activate equipment such as pump motors. The microprocessor industry brought further improvements in miniaturization of components, development of smaller and less expensive sensors and controllers, and creation of industrial local area networks (LANs) such as Allen-Bradley Data Highways. Most of these initial entrants were brought to market initially as proprietary, isolated point solutions. However, over time, manufacturers migrated such systems to network standard-based configurations such as IEEE 802.3 (Ethernet) with Internet Protocol (IP) backbones, and developed hardware/software gateways or other means to integrate their respective systems into logical model capable of being run from a central plant process control computer. These central computers, in term, supported interconnection with external systems and networks.

In the electric utility environment of today, multiple levels of ICS are used to connect generation, transmission and distribution functions into an increasingly more intelligent grid, and with broader connectivity and network connection points comes an increased risk from a cybersecurity perspective.2 Further, the attack surface of the electric power industry has been expanded through the integration of information technology (IT) systems with operational technology (OT) systems. Whereas the two were historically segregated, today they are networked in many cases.3 ICS platforms in the OT world are oftentimes built upon commercial IT operating systems. This means that vulnerabilities in the the IT environment are similarly present in the OT environment.

While on one level, a common approach to improve protection could be employed, systems in the OT environment are typically not patched or maintained to the same level as their IT counterparts, and are often dependent upon the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) for system updates due to application software compatibility. This means that OT systems will lag their IT counterparts in defensive capability. Lastly, many ICS networks do not have authentication procedures or controlled access policies, and cyber security hygiene can be poor to non-existent, making them move vulnerable.4

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security conducted an experiment ten (10) years ago at the Idaho National Laboratory in which a cyber attack was used to disrupt synchronization of a diesel generator with the electric grid.1 For those not familiar with the process, when bringing a generator on line, an operator uses a synchroscope to ensure that alternating current wave phases between the generator output and the grid are synchronized, or the generator can be damaged. Needless to say, the attacker deliberately connected the generator to the grid out of phase on a repeated basis, destroying the generator. A CNN video which documented the experiment is available on youtube at the following link:7

Let me emphasize that this was an experiment conducted a decade ago. Sophistication of malware based on zero day exploits, cross-site scripting, SQL injection, and other such methods have advanced multi-fold since 2007. There are obviously many more means for an aggressor to use when conducting a cyber attack today.

Gartner predicts that the worldwide installed base of IoT endpoints will reach over 20.4 billion by 2020.5 Because IoT devices will be able to create and deliver new data streams, each device providing a point of entry for a possible cyber attack. It is critical that, as with telecommunications networks, real-time management control systems be installed to monitor activities to enable operators to determine the nature of activities and prevent or mitigate hostile ones.

The National Institute of Standards has outlined the following recommendations for actions to improve security of ICS:6

- Restrict logical access to ICS networks and activity, using a multi-layer network topology to provide isolation

- Restrict physical access to ICS networks and devices to those having a, “need to know”

- Protect ICS components through judicious security patching, disabling unused ports (with periodic verification that action is persistent), restriction of user privilege (“need to know”), and use of both antivirus and file integrity checking software

- Restriction of data modification for both at rest and in-transit data (privileged operation)

- Employment of software to detect events/incidents

- Design for redundancy/isolation to ensure that operations can continue in the event one “train” of components is compromised

- Recover following incidents; developing and rehearsing an incident response plan to ensure recovery can be achieved in a reasonable period of time.

Many of the above are procedural actions and can be implemented with diligence and focus. Management control software requires clear understanding of the problem(s) one needs to address before conducting a selection. Design changes to achieve redundancy are probably the most difficult and time consuming to implement. The last point, that of having a clear incident response plan to recover from an issue, and rehearsing it to ensure that personnel know what to and when, is critical to survival.

For those pondering IoT and future impact, recognize that time is of the essence. Your organization’s survival could depend on it.

References

- “Cyber Threat and Vulnerability Analysis of the U.S. Electric Sector,” Mission Support Center Analysis Report, Mission Support Center, Idaho National Laboratory, Aug 2016

- “Security Attacks on Industrial Control Systems,” David McMillen, IBM Managed Services Security Threat Research Group, October 2015

- “Proactive Cybersecurity: Defending Industrial Control Systems From Attacks,” Laurie Gibbett, security intelligence.com, 25 May 2016

- “The Top 3 Threats to Industrial Control Systems,” Barak Perelman, Security Week, 30 Aug 2016

- “Gartner Says 8.4 Billion Connected ‘Things’ Will Be in Use in 2017, Up 31 Percent from 2016,” Rob van der Meulen, Gartner, Inc., Egham, UK, 7 Feb 2017.

- “Guide to Industrial Control Security,” Keith Stouffer, Victoria Pilliterri, Suzanne Lightman, Marshall Abrams, Adam Hahn, National Institute of Standards Special Publication 800-82 Rev. 2, May 2015

- “Staged cyber attack reveals vulnerability in power grid,” Youtube video; original material from Jeanne Meserve, Cable News Network, 27 Sep 2007.

Users who have LIKED this post: